The Israelites in Egypt

Código VBAO-E0009-I

VIEW:584 DATA:2020-03-20

AN ARCHAEOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVE ON THE TRADITION OF BIBLICAL EXODUS

The lands of Lower Egypt, specifically the Nile Delta region, and the Sinai Desert, located on the great peninsula in the V-shaped notch created by the Red Sea. The relevant time period from the thirteenth to the nineteenth dynasty of Egypt. These dynasties occur during the Second Intermediate Period and part of New Egypt of the United Kingdom. This time period in Egypt correlates roughly with the Middle and Late Bronze Ages and the Early Iron Age of Syro-Palestinian archeology (Table 2). Therefore, the time period of the dates for approximately 1795 - 1186 BC

The Second Intermediate Period marks a period of chaos for ancient Egypt. This period is known for the invasion of Semitic foreign peoples from Syria-Palestine to the Nile Delta, who eventually become strong enough to establish their own rulers as Pharaohs and to rule the native Egyptian kings. These Semites, called Hyksos, first enter Egypt during the thirteenth dynasty and establish their capital at Avaris (now Tel el-Dab'a). In Upper Egypt, however, the power of the Hyksos is limited because the Egyptian princes keep control of Thebes. The Hyksos comprise the fifteenth and sixteenth dynasties of Egypt and are opposed by the seventeenth Theban dynasty, one of the princes, Ahmose, finally expels the Hyksos of Egypt around 1567 BC, thus ending the second intermediate period,

The New Kingdom of Egypt, from the Eighteenth Dynasty, is the most prosperous period in Egypt and sees the pinnacle of Egypt's power. The Eighteenth Dynasty contains some of Egypt's most famous pharaohs, including Hatshepsut, Thutmose III, Ankhenaten and Tutankhamen, to name a few. The eighteenth terminal dynasty of Egypt consists of the Amarna period, an era known for Ankhenaten's failed attempt to turn Egypt into monotheism and the luxuriant tomb of Tutankhamun. The nineteenth and twentieth-century dynasties of Egypt are known as the Ramesside Period after the eleven Pharaohs who reigned over time, all by the name of Ramesses (Redford 1999: 57-58).

People known as the Israelis came to power in Syria-Palestine beginning in the Syrian-Palestinian Iron Age (about1200 BC), where they settled mainly in the mountainous region, such as the Canaanites, and finally the Philistines remained in control of the eastern coast of the Mediterranean (Mazar 2009). Much of what we know about the Israelites comes from the Old Testament Bible. However, where the Israelites came from was recently a topic of debate. It has long been believed that the Israelites left Egypt, according to the biblical account of the Exodus. Due to the lack of archaeological evidence supporting Israel's presence in Egypt or a large-scale military conquest of Canaan by the Israelites, most scholars argue that the historical narratives of the Israelites are nothing more than legends putting themselves in. " .. a supposed Egyptian context that greatly exaggerates any real role that Egypt may have played in the formulation of the Israelite people and state. "(Duty 1999: 383). However, this lack of direct evidence can be attributed to many factors, such as the popularity of Upper and Middle Egypt archeology on the archaeological investigations of Lower Egypt, the problem of parts of the strata of the Middle Kingdom being trapped under the delta water table of the Nile, and the minority status of the Israelites among their Canaanite contemporaries during the Middle Bronze Age (Hoffmeier 1996: 62).

Nowadays with genetic research, it has determined that the Hebrews are not descendants of the Egyptians, but of the Druze and Cypriots. Who are people of the fertile, or Mesopotamian, crescent. Thus it is clear that having the Hebrews (Habirus) being in Egypt, such a place is not the origin of this people. Chromosome research of the Jews, is linked to SNPs single nucleotide polymorphisms, marking patterns of chromosomal inheritance. VC4-E500

The Israelites described their own origin in the book of Exodus. The book of Exodus begins talking about a time when the extended family of Jacob (or the nation of Israel) lived peacefully in Egypt and were (Exodus 1: 7) "fruitful and multiplied greatly and became exceedingly numerous." 1 . However, the situation for the Israelites eventually becameunfavorable under the reign of a new pharaoh. To deal with the numerous and threatening Israelites, this pharaoh decreed that all male Hebrew newborns would be killed. To save his son, Moses' mother built a basket of papyrus and laid her baby floating on the Nile (Exodus 2: 3). Pharaoh's daughter discovered baby Moses and raised him as an Egyptian (Exodus 2: 5-6). Moses, however, became aware of his Hebrew past as he grew older. One day, Moses watched an Egyptian beat an Israeli worker and killed the Egyptian (Exodus 2: 11-12). When Pharaoh discovered what had happened, Moses fled to Midian, where he lived for forty years as a shepherd (Acts 7: 29-30). One day, Moses spoke with the God of the Hebrews at the top of Mount Horeb. God chose Moses as the man to deliver the Israelites from slavery. Moses then traveled back to Egypt where, with the power of God, ten plagues were sent to Egypt. Finally, after the tenth plague, which takes away the life of Pharaoh's firstborn, Pharaoh agreed to let the Israelites go. Finally, the Israelites reached the Red Sea. God "hardened Pharaoh's heart" so that Pharaoh and his army would pursue the Israelites to the Red Sea (Exodus 14: 8). God then "drove the sea with a strong east wind and turned it into dry land" for the Israelites, but approached the Egyptian army when they tried to cross it (Exodus 14:21). The rest of the Book of Exodus involves Moses receiving the Ten Commandments of God on Mount Sinai and the Israelites wandering the Sinai Desert for forty years before they reached the Promised Land. ten plagues were sent to Egypt. Finally, after the tenth plague, which takes away the life of Pharaoh's firstborn, Pharaoh agreed to let the Israelites go. Finally, the Israelites reached the Red Sea. God "hardened Pharaoh's heart" so that Pharaoh and his army would pursue the Israelites to the Red Sea (Exodus 14: 8). God then "drove the sea with a strong east wind and turned it into dry land" for the Israelites, but approached the Egyptian army when they tried to cross it (Exodus 14:21). The rest of the Book of Exodus involves Moses receiving the Ten Commandments of God on Mount Sinai and the Israelites wandering the Sinai Desert for forty years before they reached the Promised Land. ten plagues were sent to Egypt. Finally, after the tenth plague, which takes away the life of Pharaoh's firstborn, Pharaoh agreed to let the Israelites go. Finally, the Israelites reached the Red Sea. God "hardened Pharaoh's heart" so that Pharaoh and his army would pursue the Israelites to the Red Sea (Exodus 14: 8). God then "drove the sea with a strong east wind and turned it into dry land" for the Israelites, but approached the Egyptian army when they tried to cross it (Exodus 14:21). The rest of the Book of Exodus involves Moses receiving the Ten Commandments of God on Mount Sinai and the Israelites wandering the Sinai Desert for forty years before they reached the Promised Land. Pharaoh agreed to let the Israelites go. Finally, the Israelites reached the Red Sea. God "hardened Pharaoh's heart" so that Pharaoh and his army would pursue the Israelites to the Red Sea (Exodus 14: 8). God then "drove the sea with a strong east wind and turned it into dry land" for the Israelites, but approached the Egyptian army when they tried to cross it (Exodus 14:21). The rest of the Book of Exodus involves Moses receiving the Ten Commandments of God on Mount Sinai and the Israelites wandering the Sinai Desert for forty years before they reached the Promised Land. Pharaoh agreed to let the Israelites go. Finally, the Israelites reached the Red Sea. God "hardened Pharaoh's heart" so that Pharaoh and his army would pursue the Israelites to the Red Sea (Exodus 14: 8). God then "drove the sea with a strong east wind and turned it into dry land" for the Israelites, but approached the Egyptian army when they tried to cross it (Exodus 14:21). The rest of the Book of Exodus involves Moses receiving the Ten Commandments of God on Mount Sinai and the Israelites wandering the Sinai Desert for forty years before they reached the Promised Land. God then "drove the sea with a strong east wind and turned it into dry land" for the Israelites, but approached the Egyptian army when they tried to cross it (Exodus 14:21). The rest of the Book of Exodus involves Moses receiving the Ten Commandments of God on Mount Sinai and the Israelites wandering the Sinai Desert for forty years before they reached the Promised Land. God then "drove the sea with a strong east wind and turned it into dry land" for the Israelites, but approached the Egyptian army when they tried to cross it (Exodus 14:21). The rest of the Book of Exodus involves Moses receiving the Ten Commandments of God on Mount Sinai and the Israelites wandering the Sinai Desert for forty years before they reached the Promised Land.

Figuring the date of the exodus is a debate in itself. This would be much easier if the Israelites gave a name to the Pharaoh in which they were oppressed, but, unfortunately, they did not. The book of kings states that the building of God's temple began in the fourth year of Solomon's reign (conventionally dated to about 965 BC), which is also specified as being 480 years after Israel's exodus from Egypt (1 Kings 6: 1). Forty years are generally used by biblical writers to designate a generation, which would make the 480 years a possible representation of twelve generations. This would place the exodus as occurring around 1445 BC, within an interval of about two hundred years or so. Three Pharaoh-prone candidates were proposed to fit in that time period.

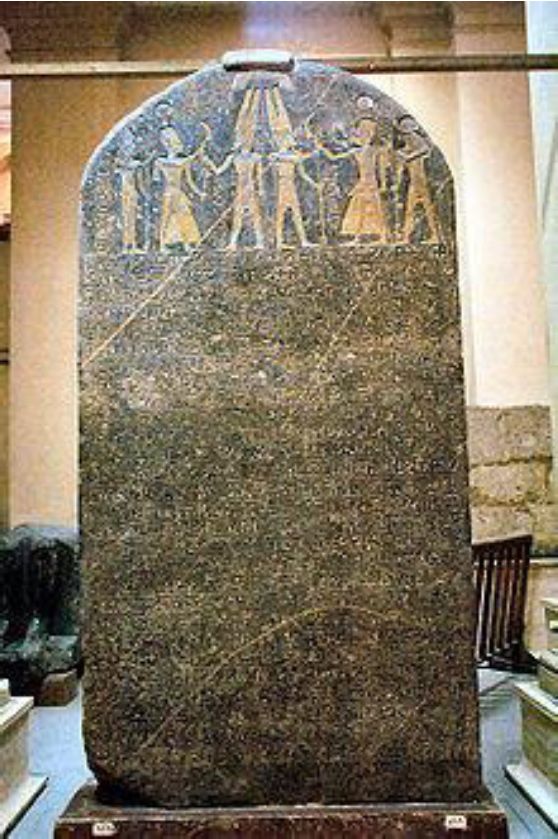

The book of Exodus states that "Egypt put slave masters over them [the Israelites] to oppress them with hard labor, and they built Pithon and Ramesses as cities of stock for Pharaoh." (Exodus 1:11). Many biblical archaeologists have related this reference from Ramses to the Ramses II capitol Pi-Ramses, making Ramses II the pharaoh of oppression. Although Rameses II is still a popular candidate among many, it may be considered unlikely due to discoveries such as the Stele of Merneptah (Figure 1) and the Hieroglyph of Soleb. The Estela Merneptah is an Egyptian monument that describes the nation of Israel as a people defeated by Merneptah. Merneptah was the successor of Ramses II, and although Israel might have been a well-established nation in the land of Israel after escaping from Ramses II, the plausibility of Israel being well developed in that short space of time is not so great as if they had been oppressed under the reign of Thutmose III or Amenhotep II, two other possible candidates. Because of this reason and because of the complications caused by the Hieroglyph of Soleb (which is discussed in more detail later in this study), the reference to Ramses is most probably anachronistic and used only in the biblical source because that is what the city was known as at the time of writing, not the time of oppression.

Figure 1. JE 31408, Estela Merneptah (from the Cairo Museum).

The reign of Thutmose Ill fits well with the approximate date of 1445 BC for the exodus. However, some argue that Thutmose III was the pharaoh of oppression and that his successor, Amenhotep II, was the pharaoh of the exodus. This is because the successor of Amenhotep II, Thutmose IV, implies in his Stela of Dreams that the firstborn son of Amenhotep II died before ascending to the throne. Some have speculated that this child died from the tenth plague described in Exodus 11: 4-5. In addition, others attribute Amenhotep's lack of military activity during the latter part of his reign to the military catastrophe of losing his army in the Red Sea during the Exodus (Bible of Archaeological Study: 98). If any of these speculations are true or not, Ramses II, Thutmose III and Amenhotep II are still the most likely pharaohs of the exodus.

The foreign Hyksos rulers of the Second Intermediate Period and the Israelites were both of Semitic origin. In making this connection, some have theorized that the expulsion of the Hyksos and the Israelite exodus is a single event counted simply as separate stories (ie the expulsion of the Hyksos depicts Egypt as the victor and the exodus depicts Israel as the victor), or O Israelite exodus is simply a surviving oral myth based on the true event of expulsion from the Hyksos (Dever 1999: 383). We may suppose that none of these speculations are true, owing to the fact that the two stories have nothing in common, except that each one involves a large number of strangers leaving Egypt. The Egyptians expelled the Hyksos during a long military campaign (Bietak, 1999), while the Israeli Exodus took weeks.

DATA ANALYSIS

Semites in Egypt

The question of the presence of ancient Semitic peoples in Egypt is indisputable. The whole focus of the Second Intermediate Period is on the foreign Semites that go beyond Lower Egypt. The capital of the Hicsos of Avaris (or Tell el-Daba) is the richest example of Semitic presence in Egypt of the archaeological record. The findings show an Egyptian Semitic presence. The tombs are of Egyptian design, but with Levantine elements. Burials are located within the settlement, which is characteristic of Syria-Palestine, and fifty percent of all male burials include Middle-Bronze Age IIA-type copper weapons and grave goods, also items indicative of Syria-Palestine. These include duckbill shafts and copper belts with engravings. In addition, donkey burials were discovered at the site,

Bietak reports an apparently gradual assimilation of Semites in Tell el-Daba. He writes: "The people who lived in this village were employed by the Egyptian crown as soldiers and possibly in other specialized professions, as leaders of caravans and merchants" (Bietak, 1999: 779). A local amethyst beetle "... demonstrates that its owner was probably a" superintendent (?) Of foreign countries "and a" caravan leader "( metjen ?). (Bietak 1999: 779). This shows that already in the thirteenth dynasty were Semite workers in Egypt, some of whom might very well have been Israelites.

However, the material culture discovered in the next stratum in Tell el-Daba is less Egyptian and more Syrian-Palestinian than before (Bietak 1999: 780). The construction of the Egyptian temples ceased and the Bronze Age style temples were built. The tombs adopted a more Syrian-Palestinian style, and deep wells were found containing offerings of remains (Bietak 1999: 780). These two different strata show that there was a period of time when the Semites immigrated to Egypt and worked as laborers before the military invasion of the Hyksos.

At first glance, this seems to be contrary to what the ancient Egyptian historian Menetho describes as a rapid military invasion by the Hyksos. In book two of his History of Egypt Manetho says:

"Tutimaeus. In his reign, because I do not know, an explosion of God hurt us; and unexpectedly, from the eastern regions, invaders of obscure race marched in confidence of victory against our land. By main force, they easily grasped it without striking; and having dominated the rulers of the land, they then burned our cities mercilessly, razed the temples of the gods, and treated all the natives with cruel hostility, slaughtering some, and bringing into slavery the wives and children of others. Finally, they named as king one of them, whose name was Salitis. He had his seat in Memphis, charging tributes from Upper and Lower Egypt, and always leaving the garrisons behind in the most advantageous positions. Above all, he fortified the district to the east, predicting that the Assyrians, as they grew stronger, One day he would covet and attack his kingdom. In the Saite [sethroite] name he found a very favorably situated city in the east of the Bubastite branch of the Nile, and called Auaris after an ancient religious tradition. This palace he rebuilt and fortified with massive walls, planting there a garrison of 240,000 armed men to protect its frontier"(Josephus quoting Manetho, Contra Apionem, book I, chapter 14, parts 73-92).

Although this appears to be a military invasion of Egypt, this is not necessarily so. Manetho describes the walls of Avaris being "rebuilt and fortified" by the invading king Hicso Salitis, as opposed to the city founded by Salitis (Hoffmeier 1996: 64-65). The important information is that the Semitic presence in Egypt did not arise with the invasion of the Hyksos kings. Earlier, the Semitic nomads existed in Egypt before that.

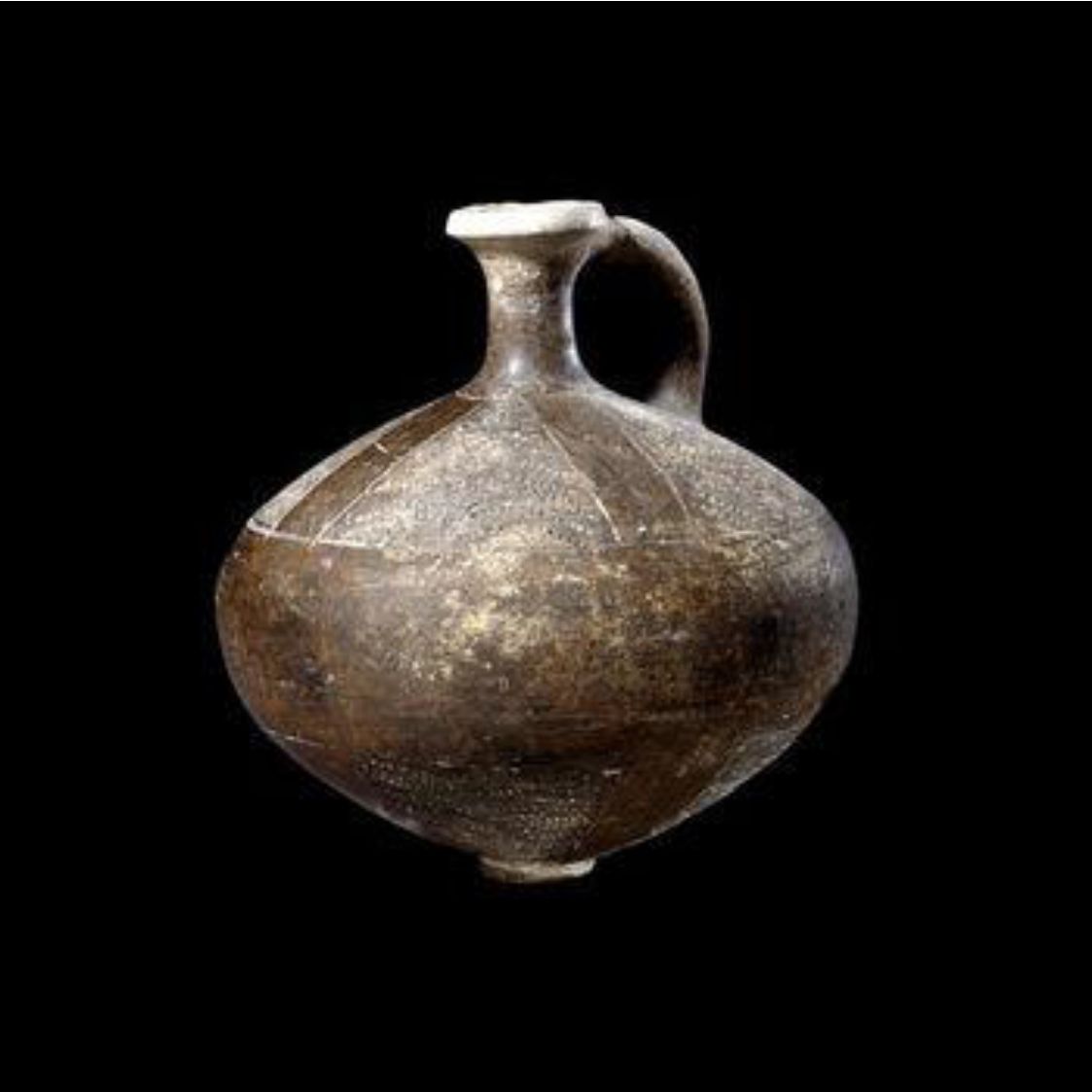

Tell el-Yehudiyeh, also located in the Nile Delta, is another example of a Semitic presence before the military invasion of the Hyksos. The modern Arabic name "Tell el-Yehudiyeh" translates as "hill of the Jew". This seems to suggest some kind of weak memory of the old Hebrew presence in the area, but it is unclear how the site got its name (Hoffmeier 1996: 67). This is where Tell el-Yehudiyeh software (Figure 2) was first discovered (Hoffmeier 1996: 67).

Figure 2. Say the-Yehudiyeh Ware from Lachish, Israel. Excavated by JL Starky, Marston Wellcome Research Expedition. British Museum ANE 1980-12-14, 10881 (accessed on Wikipedia <http://archaeowiki.org/TeU_el-Yahudiyeh_Ware>).

This type of ceramic consists of incised black ceramic with geometric patterns that has become one of the most characteristic material remains of the Semitic Hyksos. About a mile east of the tell is a graveyard. The burial mounds of clay burial mounds in the cemetery are remarkably similar to Tell el-Daba, and the remains of pottery are of Palestinian design. Archaeologist Olga Tuffnel suggests a horizon from 1700-1600 BC "She also thought that the people in these tombs were 'a poor community of shepherds'" (Hoffmeier 1996: 67).

Work conditions

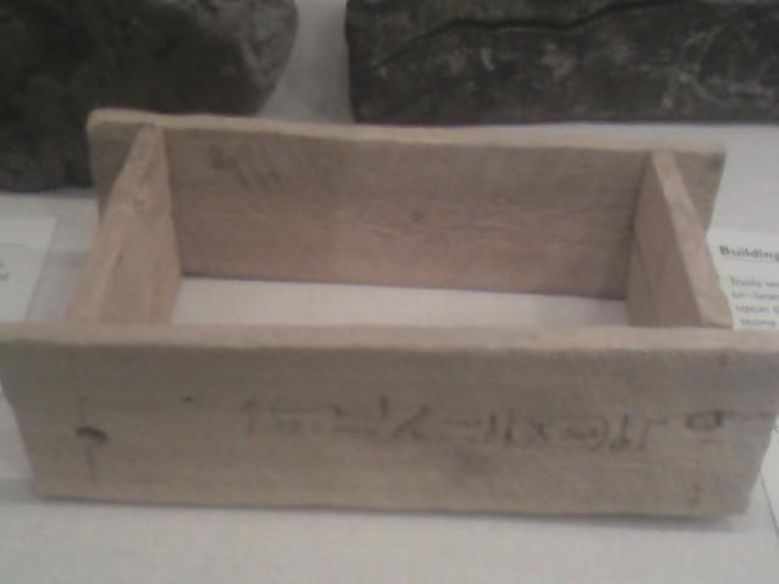

Figure 3. OIM1347, clay brick with the name of Ramesses II (from the Museum of the Oriental Institute, photo by author)

According to Exodus, the Israelites were forced to work under adverse conditions, making bricks (Figures 3 and 4) and building temples for the Egyptians. In Exodus, Pharaoh is frustrated with Moses when he requests that the Hebrews receive permission to worship God. In his fury, Pharaoh orders the drivers and officials of the people: "You must no longer supply straw to the people to make bricks; let them go and collect their own straw. "(Exodus 5: 7)

Figure 4. IOM18812, Model of a brick mold from a foundation deposit of King Thutmose III (from the Oriental Institute Museum, photo by author).

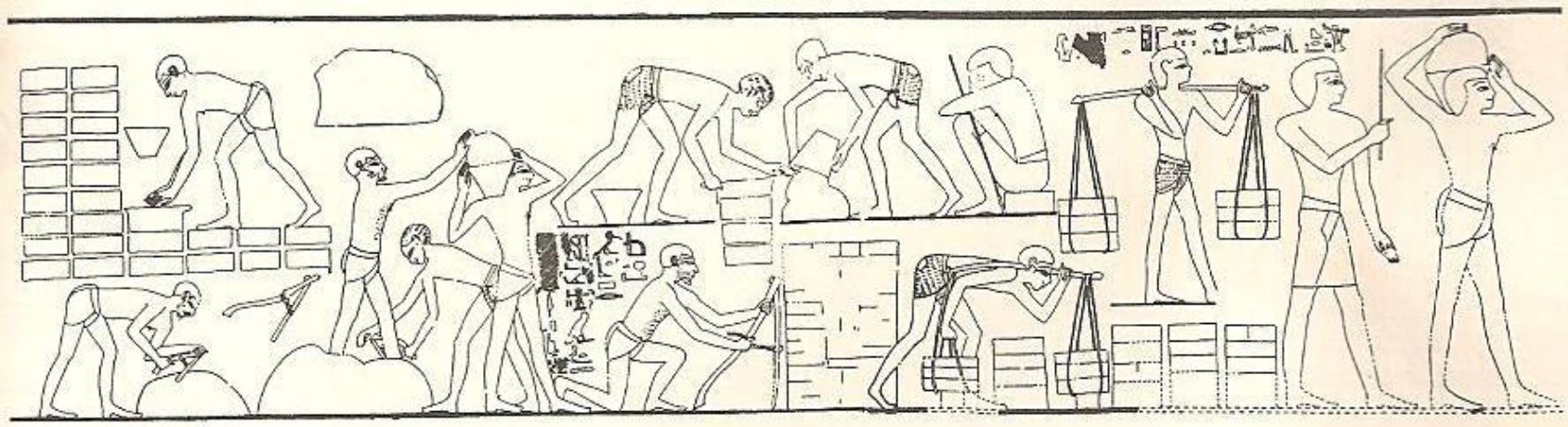

Representations of brick-making workers can be seen in the tomb of Rekhmire (Figure 5), vizier of Thutmose III (1479-1425 BC). Some theorized that these could represent prisoners of war of Canaan, since the manufacture of bricks was a common use of the Asians during the reign of Thutmés III (Chavalas, 2002). In his annals, Thutmose III records the withdrawal of thousands of prisoners of Palestine during his reign and these exploits continue until the reign of Ramses II (Chavalas 2002). This means that by the end of this period there were thousands of Asians in the Delta region, probably working on Egyptian construction projects (Chavalas, 2002). However, others have argued that these representations are nothing more than Egyptian workers.

Figure 5. Brickmakers portrayed in the Rekhmire Tomb, Thebes (from Hoffmeier 1996, New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art 1943).

In his collection, the Eastern Institute Museum has a complaint written by a scribe on a limestone piece about the harsh working conditions of some of the tomb builders (Figure 6). The complaint says: "We are extremely impoverished. All the supplies for us ... were allowed to run out. Let our Lord do for us a way to keep us alive! "(Museum of the Oriental Institute 16991). This complaint was made about the construction of the tombs in the Valley of the Queens for the sons of Ramses III and culminated in the first labor strike recorded in the twenty-ninth year of Ramses III (1153 BC).

Although this was recorded long after the proposed exodus period, it is still evidence of the harsh working conditions and lack of supplies the workers in Egypt had to face, suggesting that the exasperated Pharaoh's enraged demands were not just a problem. exaggeration added to a legendary story for dramatic effect.

Figure 6. OIM16991, Complaint of the Builder's Tomb, Hieratic (from the Museum of the Oriental Institute, photo by author).

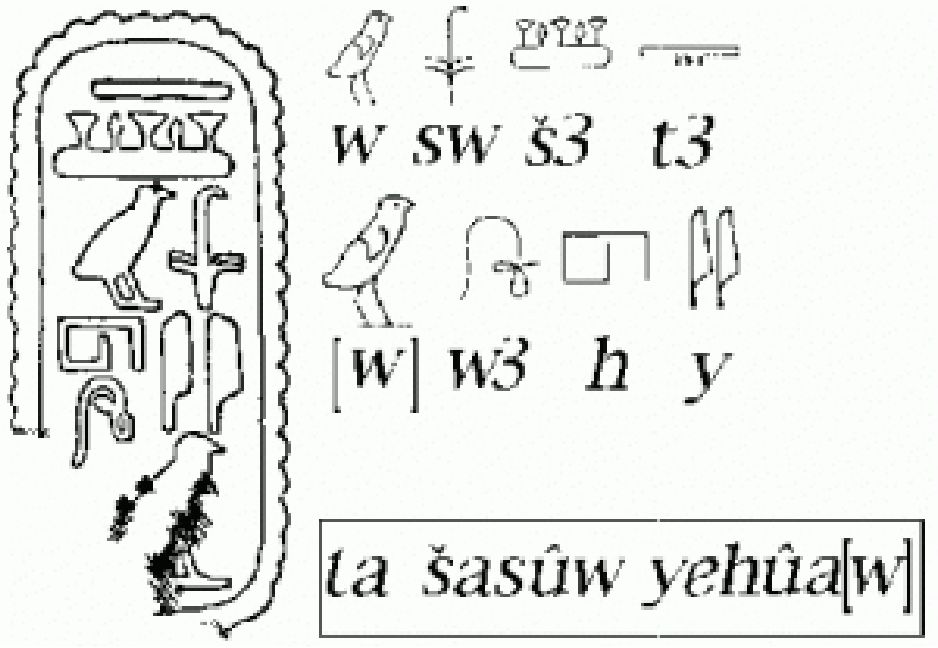

Curiously, the earliest extra-biblical account of Yahweh, the god of the Israelites, is found in Egyptian hieroglyphic texts. This reference to Yahweh (Figure 7) dates from the Eighteenth Dynasty and was discovered at Soleb, a temple built by Amenhotep III around 1400 BC and dedicated to Amon-Re (Aling and Billington 2009). This temple is located in Sudan and contains a group of texts that says "t3 Sh3sw of X" or "Land of the Shasu of X", where "X" is usually a place (Aling and Billington 2009). These texts are dedicated to reporting Amenhotep's domination of foreign peoples. One of these texts says "t3 sh3sw ya-h-waOr "Land of the Lord's Shasu." A similar list containing also the name Yahweh was found in Amarah-West in the Sudan, dating from the thirteenth century BC This list is probably a copy of that of Soleb (Aling and Billington). 2009).

Figure 7. Hieroglyph Soleb.

(from http://thebookblog.co.uk/2010/03/03/yahweh/)

The term "Shasu" is used extensively in New Kingdom texts to refer to semi-nomadic Semitic shepherds living in parts of Lebanon, Syria, Canaan and Transjordan (Aling and Billington 2009). It is possible that the "Yahweh" in these texts is referring to a place and not to the God of Israel. However, if this is true, it would be too coincidental that this is not a place with the name of the "Yahweh" of the Israelites (Aling and Billington 2009). Evidently, this evidence only works well with the date of the Eighteenth Dynasty of the Exodus, since it predates Ramses II and supposes Israel to be an established nation.

The verbal form of Yahweh was also revealed in the stela Mesha, in the letters of Lachish and in the ostraca of Tell Arad (Chavalas, 2002). Moreover, the holy name is known outside Israel long before the time of Moses. It was found in the texts of the ancient Babylonian period (1800-1600 BC) and possibly in Ugaritic texts by Ras Shamara (Chavalas 2002).

The Eastern Border Canal and Tell el-Borg

Recent archaeological excavations in the eastern part of the Nile Delta have discovered what used to be an ancient canal system that was compared to a relief of Seti I in Karnak, representing a similar channel (Hoffmeier 1996). Egyptian military fortifications were also excavated along the canal system, one of which, Tell el-Borg, is believed to be the second fortification of the Seti I relief, known as "Lion's Habitation" (Hoffmeier 2004). Artifacts found on sites show that the Eastern Boundary Channel flourished during the nineteenth dynasty. Despite this, Hoffmeier maintains that the canal may be dated to the twelfth dynasty because there are a number of historical references to a canal extending from Lake Timsah to the military fortifications in the "Paths of Horus".

Some of the many artifacts discovered in Tell el-Borg include representations of New Kingdom pharaohs that wound Semite enemies as they flee, a violently destroyed main gate and a domestic area with some tombs of Egyptian individuals (Hoffmeier 2004). Yet, possibly, the most endearing find in Tell el-Borg was a unique defensive pit, made up of nine high quality red brick courses (Hoffmeier 2004).

Excavations at Tell el-Borg and elsewhere along the Eastern Boundary Channel show that the New Kingdom of Egypt had a heavily fortified military front along the Eastern Nile Delta. The goal was probably to prevent another hicsa invasion (Hoffmeier, 1996). This could also be an explanation why God forbade the Israelites to take a route from the north out of Egypt (Exodus 13:12). Hoffmeier also believes that the biblical Pi Hahiroth (Exodus 14: 2) is located at the mouth of the Eastern Boundary Channel (Hoffmeier 1996), which is discussed more in depth in the "Exodus Route" section below.

The miracles and plagues

Throughout the course of the Exodus narrative, God uses Moses and Aaron as His agents to work miracles and bring plagues upon Egypt. It is important to keep in mind Pharaoh's divine role in reading about the plagues. In ancient Egypt, it was Pharaoh's role to keep order, or eliminate , and rid the country of anything related to chaos, or isfet (Hoffmeier 1996: 144-153). The ancient Egyptians were so obsessed with this ma'at / isfet dichotomy that dominated their works of art and literature. The plagues brought upon Egypt by Moses would have severely defied the divine authority of the pharaoh and the ability to maintain the ma'atwithin your country. At the very least, this is suggestive that the author of Exodus had an intimate knowledge of ancient Egyptian culture (Hoffmeier 1996: 144-153).

In addition, many of the same pests can also be found in Egyptian folklore. For example, Neferti's Prophecy describes the solar disk, which is covered and will not shine, much like the ninth plague of Exodus (Chavalas 2002). The story of the serpent has turned into a team and the history of water turned into blood is also found in Egyptian myths. This is another indicator of the knowledge of dominion maintained by the source of the Exodus in relation to the Egyptian context of these subjects (Chavalas, 2002).

Many scholars have tried to explain miracles and plagues by natural means. Hoffmeier follows Greta Hort by arguing that plagues are a chronological coincidence of natural phenomena (Hoffmeier 1996: 146-149). He believes that the first plague of the Exodus, in which Moses transforms the River Nile into blood (Exodus 7:19), is the result of the seasonal tides of the Nile (Hoffmeier, 1996, p. The Nile, which reaches its peak in September, usually has a reddish appearance due to the presence of Roterde,soil particles in water (Hoffmeier 1996: 146). In Exodus, the Nile is described by its blood-red color, the death of its fish, its foul smell and its unpalatable state (Exodus 7: 20-21), anything that could have been caused by millions of flagellates in water Hoffmeier 1996: 146). Frogs often invade Egypt until the end of the Nile flood in September and October. This could have been the cause of the second plague (Hoffmeier 1996: 146). The sudden death of frogs (Exodus 8:13) could have been the result of decomposing fish bacteria (Hoffmeier 1996: 146). The mosquitoes of the third plague (Exodus 8:16) were interpreted as mosquitoes that generally invade Egypt during the flood season of the Nile (Hoffmeier 1996: 146). The fifth plague, the death of cattle (Exodus 9: 3),

The hail, thunder, and lightning of the seventh plague (Exodus 9:23) not only caused damage to the plantations (Exodus 9:25, 31-32), but would have been a source of great terror to the Egyptians, since hail is something occurs very rarely in Egypt. In addition, in reporting the seventh plague, the author of Exodus makes an extra effort to note that "the flax and the barley were destroyed, for the barley was gone, and the flax was unbuttoning. The wheat and the spelled, however, were not destroyed, because they mature later. "(Exodus 9: 31-32) This commentary in Exodus is indeed consistent with the Egyptian agricultural calendar and shows a deep knowledge of Egyptian affairs that would have been difficult to acquire had the author removed for a great period of time and space of events (Hoffmeier 1996: 148). The eighth plague (Exodus 10: 4) is highly acceptable from a naturalistic point of view, considering that grasshopper pests have been a common nuisance to all who live in the Near East and Africa, even in modern times (Hoffmeier 1996: 148). The ninth plague, the plague of darkness (Exodus 10:21), can be attributed to the desert sandstorms, calledkhamsins (Hoffmeier 1996: 148). The sands of these sandstorms would have put out the sun enough to put Egypt in total darkness. The final pest, due to its selective nature, can not be attributed to natural phenomena. The tenth plague says, "Every firstborn son of Egypt shall die from the firstborn son of Pharaoh, who sitteth on the throne, unto the firstborn son of the slave, which is by his mill, and all the firstborn of the cattle. also. "(Exodus 11: 5) From the theological point of view, the purpose of this was probably to show that there was no doubt that it was a supernatural event, and therefore undermines the authority of Yahweh (Hoffmeier, 1996, 149). Moreover, as mentioned earlier, the Stele of Dreams records that the firstborn of Amenhotep II died mysteriously before ascending to the throne.

The miracle of the division of the Red Sea is undoubtedly the greatest miracle of the Old Testament. When Moses stretched out his hand over the sea, "the Lord pushed the sea backward with a strong east wind and turned it into a dry land ..." (Exodus 14:21) making a "wall of water unto his right and left of them. "(Exodus 14:22). However, when Pharaoh's army tried to cross the sea, "water flowed back and covered the chariots and horsemen" (Exodus 14:28). Though intriguing, many consider it a myth or a children's tale. However, physicist Colin Humphreys argues that a natural phenomenon known as "wind deceleration" satisfies this story. This rare occurrence happens when a strong and constant wind blows through a long body of water that is relatively long in relation to its width, causing the water level to fall significantly on the windward side while a water wall is pushed up on the opposite side (Humphreys 2004). If the wind continues to blow through the length of the sea, the drag of the water causes a space to open and expose the sea floor. Although rare, this phenomenon is observed today in places where wind conditions and water layout are perfect (Humphreys, 2004). Exodus 14:21 describes a "strong east wind" as the cause of the division of the sea. As the ancient Hebrew has only specific words for the four cardinal directions, "east" could represent a northeast wind, which would have caused the occurrence of this phenomenon in the Gulf of Aqaba (Humphreys, 2004). Unfortunately, this theory only satisfies the Theory of the Central (or Arabic) Exodus Route,

However, natural explanations of these events in Exodus do not make them less miraculous. "The ancient Israelites believed that their God worked with and through natural events" (Humphreys 2004). What made these events miraculous was their timing: for example, the Red Sea separated well in time for the Israelites to escape Pharaoh's army and was closed as the Egyptians tried to pass. Therefore, these natural explanations can serve to make miracles more, no less believable.

Bless_Jonathon_Thesis.pdf

BUSCADAVERDADE

Visite o nosso canal youtube.com/buscadaverdade e se INSCREVA agora mesmo! Lá temos uma diversidade de temas interessantes sobre: Saúde, Receitas Saudáveis, Benefícios dos Alimentos, Benefícios das Vitaminas e Sais Minerais... Dê uma olhadinha, você vai gostar! E não se esqueça, dê o seu like e se INSCREVA! Clique abaixo e vá direto ao canal!

Saiba Mais

-

Nutrição

Nutrição

Vegetarianismo e a Vitamina B12 -

Receita

Receita

Como preparar a Proteína Vegetal Texturizada -

Arqueologia

Arqueologia

Livro de Enoque é um livro profético?

Tags

tag